The Butterfly Effect

When I was at university, I had an older teammate named Osman Lake. Osman was an 800-metres runner, one of the best in the league, and it seemed to me he always knew how to win.

One of his favourite tactics was to take the lead early, then … just keep it. Competitors would come up alongside, trying to pass, and Osman would speed up just enough to hold them off. It was certainly not the most efficient way to run, but it worked for him. A lot.

I suspect there was something in Osman’s brain telling him, “Don’t let them past.” His brain was winning those races.

I was different. I won more than my share of races, but often, I needed to learn a lesson first. I needed to lose to understand how to win the next time.

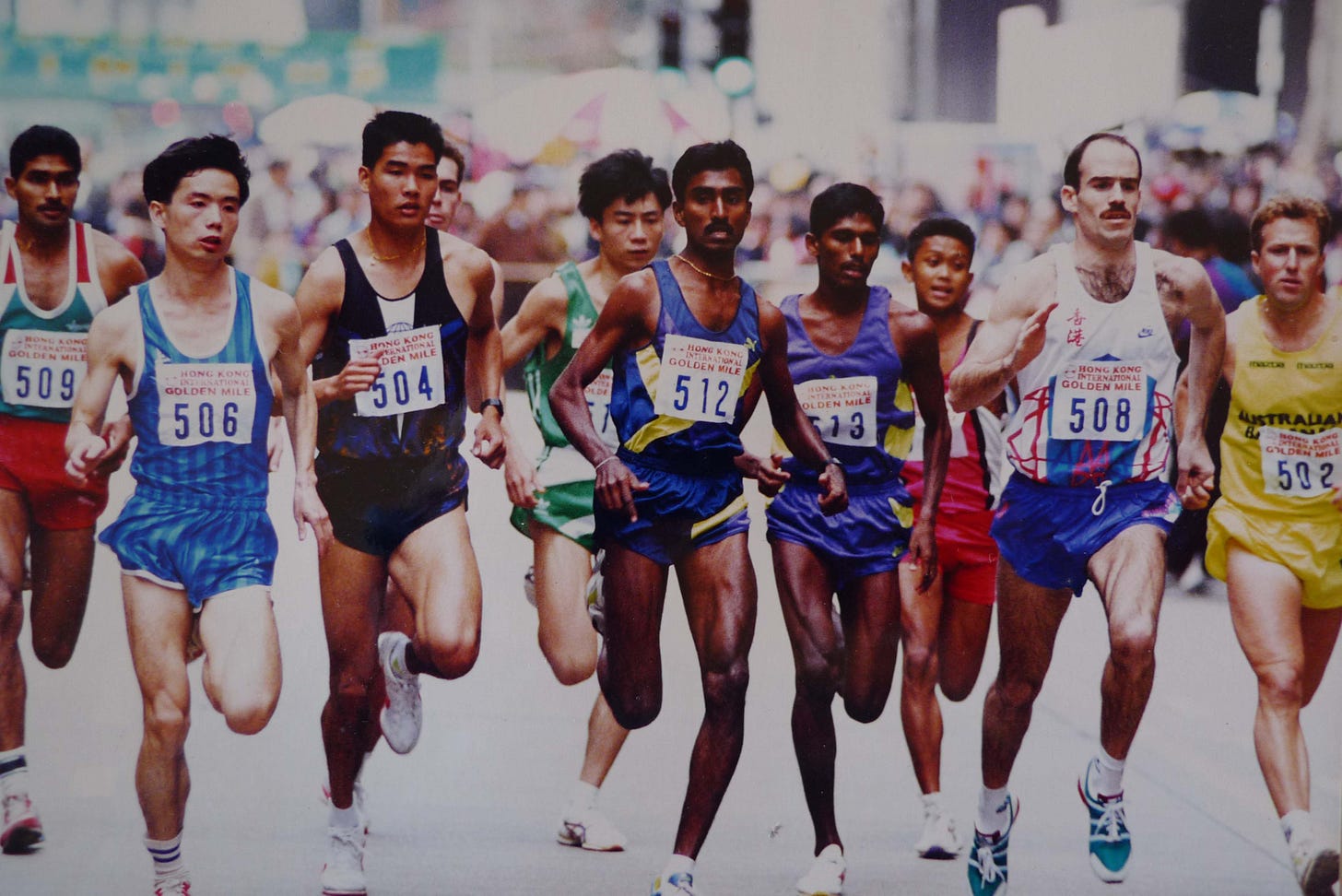

After university I took a few years off from competitive running, only resuming after I moved to Hong Kong. For a few years I ran on the track, on the roads up to 10 kilometers, and occasionally in longer (but not too long!) trail races such as Mount Butler. And I mostly won.

At a certain point, I qualified for permanent residency, which gave me the opportunity to compete for Hong Kong at the world level, in world championships and at the Olympic Games. Talking over my Olympic qualifying options with my training partners, we agreed that the marathon was my best chance not only to qualify for the Olympics, but also to not humiliate myself in front of two billion television viewers (because the cameras would be on the frontrunners, not me) if I qualified.

The only problem was that I had never raced farther than 15 kilometres.

To gain experience, I entered a few half marathons, of which there were quite a few starting up in Hong Kong at that time (in the mid-1990s), and my first half marathon was a win, though I was absolutely destroyed afterwards.

In those days all the (road) half marathons were held out in the northeastern New Territories, on hills. But that first race was a good start, and I continued to pile on the miles (kilometres) in training and plan my marathon debut.

My second half marathon was another hilly one, and with one race under my belt, I felt more confident. I ran with one of my main road racing rivals, Lee Kar-lun (for the Singaporeans, he married Singaporean marathon champion Toh Soh Liang!), until with around two kilometres to go, on one of the final hills, Lee indicated to me that he could go no faster, and that I should go ahead.

I thought to myself, “I think I will go faster!” And I shifted gears dramatically on that last steep uphill, somehow pushing my engine past the red line and blowing up. I wish there had been video footage, because it happened very quickly and must have been funny to see. As I crested the hill, literally trying not to vomit, Lee ran past me and down the other side to snatch the win.

After I finished, I shook his hand and said, “You got me.” He just smiled.

Several races later he tried it again, but I had learned my lesson, maintained my pace until I was within sight of the finish line, and pulled away easily for the win. Afterwards, I said to Lee, “Not twice.” He smiled again.

Experienced runners know that racing is mostly a straightforward proposition. If you have done the work, and have talent, you may have a chance to win (or place, or finish in accordance with whatever goal you have set for yourself).

If you are talented but someone else has more talent, you are likely to lose. Unless you have done the work and your talented opponent has not. However, even if you have done the work, and your opponent has not, if he/she is much more talented, you will still very likely lose.

This happened to me in a race some years ago, also in Hong Kong. For a number of years, I was the adidas King of the Road in Hong Kong (where the company started its King of the Road series in Asia), and one year they decided to bring in top athletes from around the region to compete in the final race. No one in this group worried me, except a runner from mainland China who was reputed to have a 10-kilometer best of around 28 minutes, well over a minute faster than my own personal best. I don’t care how well you’ve prepared for your 10K; if you’re running under 3:00 per kilometre, and up against someone who is almost two minutes faster, you’re gonna lose.

And so it was. After the start, the Chinese runner joined me and my training partner Kjeld in a 3-man lead group, and for the first two kilometres, we ran together, behind a bicycle that was showing us the route.

At that point, Kjeld (a pretty handy runner, with a 2:20 marathon best) said to me, “I wonder if he knows he doesn’t have to run with us?”

Seconds later, although I am certain he spoke no English at all and had not understood Kjeld’s remark, the Chinese runner took off as though we were standing still. He put around 100 meters on us during the next 400 metres, and Kjeld gasped, “Buh-bye.” And we didn’t see the Chinese runner again until the awards ceremony (he got to stand on the top step; Kjeld and I took the lower steps).

I started thinking about winning recently because my daughter Saya is running well. In middle school, she had success, but last year, in advance of entering high school, she told me she was going to quit running because she didn’t like the feeling she got before races. She told me she was thinking of taking up kyūdō, Japanese archery. “Oh, that looks cool,” I said. [And it does look cool.]

If you have ever competed in a sport, you know the feeling: butterflies in your stomach.

When I was at university, I had a friend named Adam. Adam ran for another school but since we ran the same event we often warmed up together and competed against each other. One year at the Penn Relays, where Adam was scheduled to run the open 1500 metres and I was anchoring my team in the sprint medley relay, Adam grabbed my arm and said, “You’ve got to warm up with me. I’m too nervous to do it alone.”

So we jogged and stretched together and went into the holding area at roughly the same time since his race was due to go off just before mine. I was standing by the track stripped down and ready to run during Adam’s race and had a great view of him upsetting the field (including one of the world’s best in the event) and recording the fastest time in the world to date for that particular year.

Adam had stormed down the home straight and run 3:36, a personal best (PB) by four or five seconds and a fantastic win. [At that time the world record was only 3:29.] He staggered over to where I was waiting to go onto the track and nearly collapsed into my arms. I was thrilled to have seen my friend achieve such a spectacular performance and congratulated him excitedly. He said only, “God, I’m going to be sick,” and threw up in the bin that was luckily right next to me.

Later that year, my father and I ran into Adam on the street in New York and after the usual greetings and small talk I asked him how his running was going. I expected to hear of trips to Europe, new PBs in the low 3:30s and of plans for an Olympics bid. Instead, he said, “I’ve quit running. I’ve never felt better.”

Adam was the most talented runner I ever met – he once set the American indoor record for 1000 metres in a triangular meet because he miscounted the laps, kicked for home, and then had to take off again like a startled rabbit when the bell rang to signal one lap to go – but he hated racing. He didn’t hate running – but in a race he found himself driven by whatever drove him ... to a place he did not like.

When I was running track in high school and at university, I had butterflies all the time, and in my first few years of racing when I lived in Hong Kong, I often had them before road races (though not before too many track races, where the competition was not as good).

But I don’t get them anymore, even when I’m fit enough to race. Why not? I thought about it and found the answer interesting ... in my experience, butterflies dance around in your stomach when 1) you’re fit enough to have high expectations of your performance or 2) the race is important.

Earlier this year, a few weeks after she started high school, I asked Saya how archery was going. She replied that she had decided Japanese archery wasn’t for her. “Why not?” I asked. “It’s very quiet,” she replied.

She had decided to go back to running track, and after a month of training, to catch up with her teammates, she started racing again. She and I had had a short talk about “butterflies”, I had explained that it’s normal to feel anxious before races, and she seemed excited to be getting back into competition.

In the few months since then, she has done (very) well, and is excited about taking her running as far as she can. From what I can see, that could be quite far, but if someday Saya runs the fastest time in the world to date that year in the 800 metres, and after finishing, nearly throws up on my shoes and says, “I want to quit,” that will be fine.

Many people think nervousness before a race is a bad thing, an energy waster, perhaps, or a sign of weakness. Certainly, some athletes can be paralysed by fear and are chronic underachievers but, for the majority of us, nervousness can translate directly to desire – desire to win – or fear of losing, which can be an even more powerful motivator.

My friend Adam was an exceptional runner, and someone for whom butterflies were a major problem. For the rest of us, I think, a stomach full of butterflies on the start line is an asset.

Exactly. A valuable signal to self. “Pay attention! This is serious.” As the late notorious British MP observed: “Always make a speech on a full bladder.”

Yup. Butterflies are for a reason. To tell you it’s serious and you need to focus. You need to know how to cope with them. Some do. That btw is one sign of a good crisis manager in business—or indeed life