Many years ago I competed in the New York City Summer 4-Mile Championship. At the time I was a university track runner, and four miles (6.4 kilometers) was out of my comfort zone, but it was something to do on a Sunday morning during the summer holidays. The race was organized by the New York Road Runners Club, and (for those who know Central Park) the start was on the Park Drive, at 90th Street and Fifth Avenue. The course was one loop, cutting off the loops above 102nd Street and below 72nd Street.

It was a beautiful morning, and after the starting horn had blared, a small group formed at the front. One guy pulled away quickly, and because I wasn’t confident I could stay with his pace, I fell in with a couple of guys running a more sensible tempo.

The leader pulled steadily away, and as we crossed the park at 102nd Street and headed back downtown, I started to think about whether I could beat the two guys I was running with. At this point, two miles in, the leader was only occasionally visible, when the road straightened, and I had written off the idea of winning.

At 72nd Street, the course turned east, and the “chase pack” was down to two of us: me and a tall Brit, probably a few years older than I was (I was 19, I think). I was feeling comfortable, and I knew that when we turned back uptown (along the back of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), there was a mile remaining to the finish, including a big hill.

I said to the Brit, “I think I may go after him. You interested?” He said, “I’m fine at this pace, mate. Good luck.”

So I turned up the pace a notch, and pushed up the hill.

At the top, I could see the leader, but he was still around 100 meters ahead, a long way, with time running out.

But I kept pushing, and when I made the slight left onto the final straight, around 250 meters from the finish, I saw that I was only around 40-50 meters behind.

I was already pushing as hard as I could, but tried to squeeze a little more out of my legs, and as we came into the final 100 meters, a roped-off chute with spectators on both sides, I thought, “I might be able to do this!”

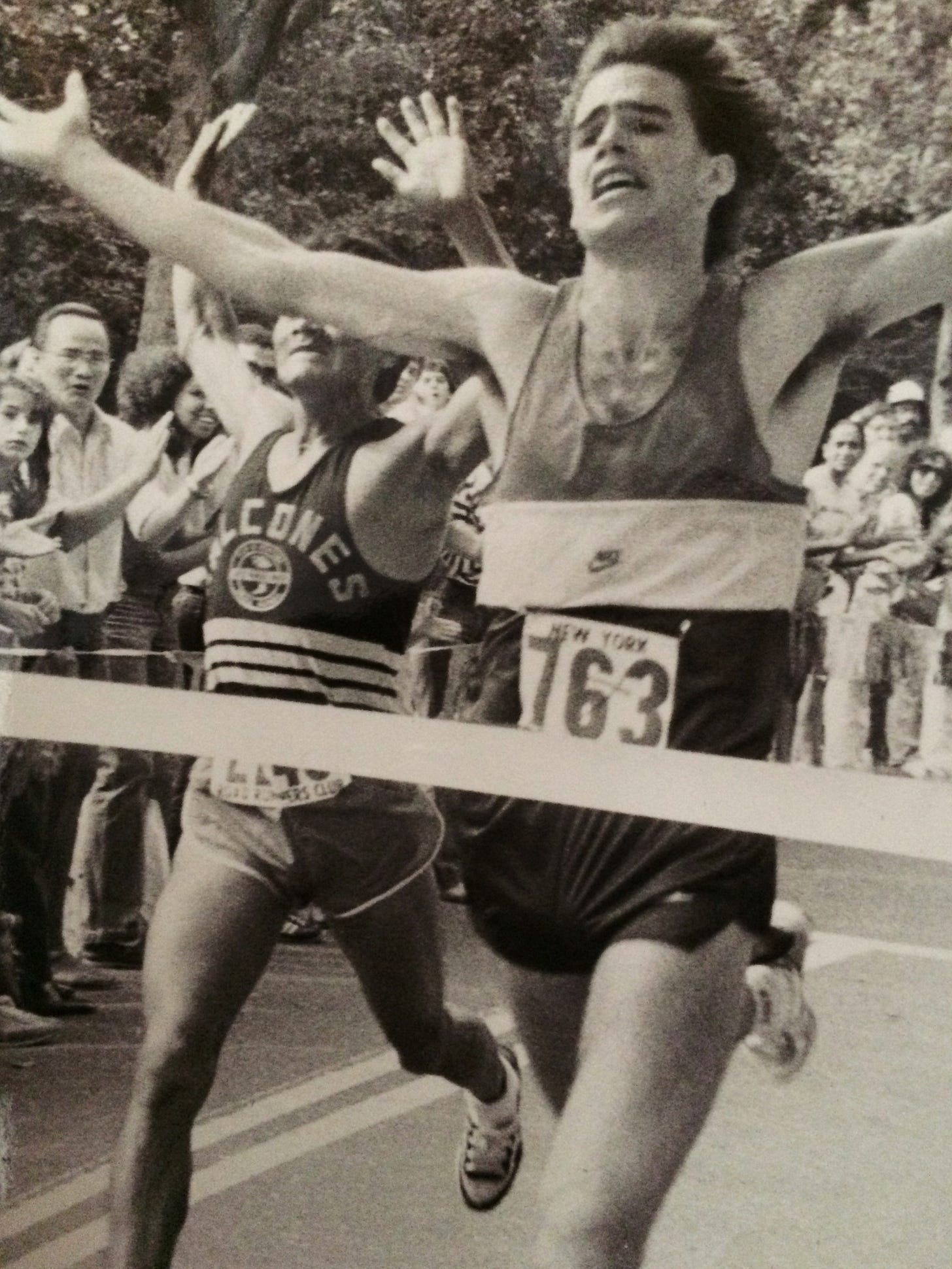

You’ve seen the photo above, so you know how it turned out. I overtook the leader with two steps to go.

His arms are raised because he thought he was about to win, having led the whole way. I have another photo, taken a quarter second later, and in it he has thrown down his arms in frustration.

That was a fun race, and a good win. The next day, I saw my name in The New York Times, and learned the name of the second-place finisher. Placido Cruz Martin.

Placido was in his 30s at the time, an immigrant from Colombia and a solid club runner who would go on to win the Yonkers Marathon in 1985, and eventually run under two hours 30 minutes for that distance.

Fast forward 15 years and I am living in Hong Kong, but back in New York visiting my parents. Their place was close to Central Park, and that was my regular training loop. On one run I fell into step with a local guy, running fast, and as we circled the park he caught me up on New York City elite running gossip.

He told me, for example, that Jesse McCutcheon, an old track rival, had broken up an attempted rape in the park, while out for a run one evening. He’d heard a woman scream for help and chased away her attacker. “Jesse, man, he’s a hero,” said my running partner. Back at that time, New York City was a lot less safe than it is today, and the case of the Central Park Jogger was still fresh in people’s minds.

Then he said, “Hey, you remember Placido Cruz Martin?”

Sure I did.

“Placido was in that Avianca crash a few years ago! He lost his leg!”

On January 25, 1990, Avianca 052 from Bogotá to New York, via Medellín, ran out of fuel after a failed landing attempt and crashed in Cove Neck, on Long Island. Eight of the nine crew members and 65 of the 149 passengers on board were killed.

Placido Cruz Martin was thrown clear of the plane, and woke up on the ground outside with a broken leg, two broken ankles, a broken hand and facial lacerations. In the three months following the crash he underwent five operations, including a bone graft to unite the bones in his leg.

He hadn’t lost his leg, I discovered when I did some research, but his fast marathon running days were over.

Placido was lucky to survive when 73 passengers and crew members did not, but in another sense, he was unlucky.

Because although 77 people have been killed in commercial aviation accidents since Donald Trump was inaugurated president on January 20th, air travel remains – statistically – very, very safe.

In this decade, until Trump’s inauguration, only 19 people had been killed in commercial plane crashes involving U.S. carriers or U.S. airports.

During the entire decade of the 2010s, only 21 people died in commercial plane crashes involving U.S. carriers or U.S. airports.

The death toll in 2000s was higher, at 773, but included the four plane crashes of September 11, 2001.

The 1990s were more dangerous. During that decade, 1,358 people died in commercial plane crashes involving U.S. carriers or U.S. airports.

And 415,336 people died in motor vehicle crashes on U.S. roads.

Wow, what a story! Not the best way for Plácido to quit running at all!